Latin America on Screen

Latin America on Screen: Film as a Complement to Teaching Regional Geography.

W. George Lovell

Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario.

In this exploratory foray, I comment 1) on an evolving body of literature at the nexus of geography, film, and pedagogy before 2) evaluating and contextualizing twenty-two feature films by twenty-one different directors that conjure up perspectives on Latin America in all its tangled complexity.

Contents: Contact, Conquest, and Colonial Experiences

- Como Era Gostoso o Meu Francés/How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman (1971)

- Aguirre: Der Zörn Gottes/The Wrath of God (1973)

- La Ultima Cena/The Last Supper (1976)

- The Mission (1986)

- Cabeza de Vaca (1990)

- 1492: Conquest of Paradise (1992)

FILM SYNOPSES [1]

Contact, Conquest, and Colonial Experiences

Como Era Gostoso o Meu Francés/How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman (1971), directed by Nelson Pereira dos Santos.

A year before this unusual feature was made, in an interview with Randal Johnson (Burton, 1986), Brazilian film-maker Glauber Rocha declared:

The first challenge to be thrown at Brazilian cinema is this: how to win over the public without using the American models that today predominate, even in Europe. What is the point of struggling to create a cinema that says nothing, good or bad, about the specific culture to which it belongs? (p. 105)

How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman is specific, and not just in a playful cultural sense. On one level it may be viewed as historical reconstruction, a portrayal of the encounter between Indians and Europeans in sixteenth‑century Brazil. At another level it is subtle parody, a political statement made at a time of censorship and repression when anything bolder would have been problematical, probably suicidal, for the filmmaker.

Jean, a shipwrecked French sailor, walks along a solitary shore. His fellow countrymen are attempting to carve out trading footholds along the coast of Portuguese‑claimed Brazil, where dyewoods that fetch good prices in Europe are plentiful. He is captured by the Portuguese, only to fall into the hands of a local Tupinambá tribe. His claim to be French is not taken seriously, but he is kept alive, Jean’s captors even furnishing him a partner, Sebiopepe, whose name in Tupi translates as “bloodsucker.” He lives by his wits, goes even more native than Cabeza de Vaca (see synopsis below), and fights on the side of his adopted people against their enemies. He then strikes a deal with a Portuguese merchant and plans his escape from captivity, attempting to lure Sebiopepe along with him. But the tribe who bequeath him hut, hammock, wife, and love have in mind a different end.

As in Aguirre (see synopsis below), the line between civilization and barbarism is illusory, and soon vanishes. The dreams that Europeans have of fame and fortune fail to materialize in a New World that simply won’t conform to Old World expectations. A classic piece of film-making wrought in the “tropicalista” mode of Cinema Novo, How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman holds up remarkably well. Sixteenth‑century Europeans were disgusted at cannibalistic tendencies on the part of indigenous communities, especially in Brazil, yet accepted such traumas as the terror of the Inquisition as part of the natural order. Double standards prevailed, and still abound. Here, in the hands of Nelson Pereira dos Santos, cultural contact resembles more black comedy than Black Legend. An interview with Pereira dos Santos conducted by Julianne Burton (1986) contextualizes the film aesthetically and historically, as does the interview Burton (1986) transcribed and translated after her tête à tête with filmmaker Carlos Diegues. Davis (2001) also offers an incisive critique. The film’s factual basis, on the life and times of German sailor Hans Staden, spawned another film by that eponymous name, directed by Luís Alberto Pereira (1999).

Aguirre: Der Zörn Gottes/The Wrath of God (1973), directed by Werner Herzog.

Werner Herzog’s most renowned film reconstructs the entrada into the heart of South America in search of the fabled El Dorado organized by the Spanish colonial regime in 1560. After a successful descent from the Peruvian Andes to the headwaters of the Marañon (Amazon), the expedition, led by the weak and vacillating Pedro de Ursúa, is plagued internally by strife and dissent. The tyrannical Lope de Aguirre emerges as leader, played in the film by the maniacal Klaus Kinski (1926-1991) in a role tailor-made for him. Opposed to Ursúa’s idea of establishing a settlement to function as a sedentary base for exploration, Aguirre lobbies for rafts to be built and for the party to venture downstream. Ursúa is overthrown, put on farcical trial, and hanged. Along with the men he has coerced into following him, Aguirre then floats off in pursuit of the Hispanic dream. Visions of fame and glory disintegrate in the face of apathy, ineptitude, disease, hunger, continuing conflict from within, and the megalomania that fuels Aguirre’s mind. Along the banks of the river, the natives watch and wait as the dream unravels. The film ends with Aguirre, adrift on the oppressive and never‑ending Amazon, declaring his wrath on creation.

Although exercising no small artistic license, Herzog succeeds in imparting a palpable sense of time and place. The film, shot on location in the Andes and the Upper Amazon basin, is visually stunning: rich, lush, and teeming landscapes fill every frame. Quechua‑speaking Indians are used as carriers in the ethereal opening frames. Accustomed to the bracing cold of the highlands, these unfortunate souls quickly perish in the suffocating heat of the lowlands. In all their sophisticated finery, Ursúa’s mistress and Aguirre’s daughter accompany the expedition, as does a priest who sees no contradiction in lusting for wealth while spreading the Word of God. Civilization has come face-to-face with barbarism, but as the film ends it is difficult to tell which is which.

Though Herzog researched and scouted things out before filming, several factual infelicities are apparent. Foremost is that, in reality, Aguirre and his fellow rebels drifted all the way downriver (either on the Amazon alone or on the Amazon and Orinoco drainage systems), reached the Atlantic, sailed west to the island of Margarita off the coast of Venezuela, and eventually invaded Peru. There Aguirre was killed by forces loyal to the Spanish Crown. His body was cut into pieces and his head impaled on an iron spike to serve as a public example of the fate awaiting all those who rebelled against the authority of the King of Spain.

In the Archivo General de Indias in Seville, sixteenth‑century documents relating to the Aguirre rebellion are a challenge to peruse. If they can be believed, Herzog certainly did not exaggerate the intensity of the violence by which Aguirre lived, ruled, and died. Galeano’s Genesis (1981/1985) captures Aguirre’s triumphs and travails in four captivating vignettes. Minta (1993) pieces together a compelling reconstruction of Aguirre’s rampage. A decidedly more revisionist portrayal of him, as a misunderstood rebel of revolutionary mettle, is offered by Balkan (2011).

La Ultima Cena/The Last Supper (1976), directed by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea.

Tomás Gutiérrez Alea (1929-1996) is still Cuba’s most internationally acclaimed and prolific director. Studies at film school in Italy saw him return to Cuba and participate in the making of El megáno (The Charcoal Worker, 1955), a documentary-style feature that was banned upon release by the Batista regime. He subsequently directed more than twenty films, among them the biting critique of Cuban revolutionary society, Death of a Bureaucrat (1966), and his pro-gay Strawberry and Chocolate (1993). El Titón, the “Titan” as he came to be called, is perhaps best known for his rumination on culture and imperialism, Memories of Underdevelopment (1968), as masterly a cinematic exposition of the subject as the exegesis of Edward Said (2000).

In The Last Supper (1976), Gutiérrez Alea leans on events that took place on a sugar plantation near Havana in 1795, as the opening credits make clear. The five key days of Semana Santa, Easter or Holy Week, see all who inhabit the estate of Count Bayona play out parts of the life (and death) of Jesus Christ.

Miércoles Santo (Ash Wednesday) begins with Don Manuel, the plantation overseer, setting the dogs on a runaway slave, Sebastián. The Count arrives to inspect his domain. He is concerned about his spiritual welfare, as conversations with the plantation’s resident priest reveal early on. Sebastián is caught and punished. Allusions are made to the slave revolt in Santo Domingo, the island today shared by Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Fear of a similar uprising in Cuba is fuelled by the Count’s French-speaking plantation manager worrying that importing more slaves to increase sugar production will inevitably mean that blacks will outnumber whites and mulattos. “Este no es Santo Domingo,” the Count asserts confidently. “This is not Santo Domingo.” Apprehension heightens, however, when the Count asks Don Manuel to pick twelve slaves to join him at supper the following day.

Jueves Santo (Maundy or Holy Thursday) sees the chosen twelve dine with the Count after he washes and kisses their feet. The Count’s resident priest is mystified. Don Manuel leaves in disgust. The slaves eat and make merry, extracting from the Count a guarantee that no work will be performed the following day, the most important day in the Catholic calendar. The priest is at least happy that no coerced labor will sully the sanctity of Viernes Santo, Good Friday.

Good Friday, however, is just another day for Don Manuel. The sugar quotas have to be met. His insistence on forcing the slaves to work ignites rebellion, which runs its course through Sábado Santo (Holy Saturday) and terminates on Domingo de la Resurección, Easter Day.

Galeano’s Faces and Masks (1984/1987) captures the drama of The Last Supper in one of his most riveting vignettes. The cross and the sword appear not as symbols of Christian compatibility but rather icons of mutual exclusion.

The Mission (1986), directed by Roland Joffé.

A spectacular piece of film making, The Mission explores the repercussions of the geopolitical need, from the point of view of imperial Spain and Portugal, to replace the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) with the Treaty of Madrid (1750). The action takes place amid landscapes of breath-taking beauty, among them the waterfalls of the Iguazu River, where the borders of Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay touch. Above the falls is where Guaraní Indians have retreated to, there in the forest creating a culture of refuge, a culture of resistance against European intrusion, whether the intruders are Portuguese slave raiders (bandeirantes) or dedicated Spanish Jesuits undertaking “spiritual conquest.” The complexities of the situation are illustrated through the personalities of the three main protagonists: a Jesuit missionary named Father Gabriel, played by Jeremy Irons; a cuckolded mercenary named Mendoza, played by Robert de Niro; and a Catholic envoy for the Pope, played by Ray McAnally. At the very close of the film, after all the credits have rolled, the papal delegate stares us in the eye with a look that cuts like steel. The first man believes in the power of love, the second in the power of the sword, the third in the power of the Church – even though he finds himself with far more on his conscience than he had bargained for. Against all three conflicting forces the Guaraní eventually come to ruin, but some young people escape, the survivors who will carry on the ways of the ancestors.

The visual appeal of the film is complemented by a symphonic soundtrack composed by Ennio Morricone, perhaps better known for his jingles to Clint Eastwood “spaghetti westerns.” Here Morricone blends traditional South American Indian airs with baroque‑style incantations. The effect is plaintive and cathartic, “Gabriel’s Oboe” and “Miserere” most of all. In some scenes the mix of landscape, drama, and music is particularly moving.

There is a sizeable literature on the Jesuit reducciones in what today are the republics of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, and Paraguay, which Caraman (1996) has perused to comprehensive effect. An interview with filmmaker Roland Joffé (Dempsey, 1987) offers unique insight into the making of The Mission, critiqued incisively by Scholfield Saeger (1995). Galeano’s Faces and Masks (1984/1987) furnishes three emblematic vignettes. The carnage at the close of the film is a re-enactment of the Battle of Caybaté, in which 1,500 Guaraní and a handful of Jesuits were killed resisting the joint forces of Spain and Portugal. The two crowns were assisted in their victory by native guides and auxiliaries hostile to the Guaraní, who wished to remain under Jesuit protection. What native peoples desired, however, was of no import in the agenda of empire.

Cabeza de Vaca (1990), directed by Nicolás Echevarría.

Before turning to feature film-making, Nicolás Echevarría was regarded as one of Mexico’s finest documentary film-makers, many of his titles in this genre dealing with indigenous issues. Echevarría leans heavily on his documentary laurels in Cabeza de Vaca, his first feature film, a meticulous, fine-grained creation that revels in ethnographic nuance and detail.

The film takes its title, and its plot, from the remarkable story of Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, who in November 1528 was washed ashore, some reckon near the present site of Galveston in Texas, after the doomed expedition to Florida led by the conquistador Pánfilo de Narváez. Along with two Spaniards and a Moorish slave, Cabeza de Vaca trekked some 6,000 miles across Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and northwest Mexico before reaching Mexico City in July 1536. Eight years of wandering saw Cabeza de Vaca complete a journey that was as much one of spiritual self-discovery as dogged self-survival. When he eventually runs into his fellow countrymen, he soon realizes he now has little in common with them. Along the way he “goes native” to such an extent that he gains the healing powers of a shaman. After such knowledge, a return life as a Spanish nobleman engaged in the Christian pursuit of empire is no longer possible.

Long’s telling of the tale (1936/1987) has been fleshed out by the meticulous research of Adorno and Pautz (1999), and also an inquiry published three years before Long’s poetic interlinear by Bishop (1933).

1492: Conquest of Paradise (1992), directed by Ridley Scott.

Of all the hoopla surrounding the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s historic landfall, Ridley Scott’s 1492: Conquest of Paradise was perhaps the most hyped. The gutsy Scott takes not only his subtitle but also his heavily revisionist thrust from a book by Kirkpatrick Sale (1990) by the very same name. Like Sale, Scott portrays the meeting of natives and newcomers primarily as the latter’s sustained violation of the former’s assumed and exaggerated innocence. Scott’s film, though factually romanticized and narratively uneven, lends itself to critical examination of contentious issues related to the Old World’s invasion of, and enduring impact on, the New.

The film begins, appropriately enough given this forum, with a geography lesson. Seated with his son on an eastern Atlantic shore, Columbus looks west into the sunset as a ship disappears over the horizon. He has come to believe that the world, like the orange he is peeling, is round – even though he realizes that the Inquisition can have people burned at the stake for holding such beliefs. The lucrative spice trade of the Indies, Columbus reckons, can be secured not only by sailing the known route to the east but also by risking an unknown route to the west. It becomes Columbus’s mission, then obsession, to convince his many detractors (and few backers) that he is right.

Scott structures his film in three parts. Part 1 reconstructs key episodes prior to the voyage: we witness, among other incidents, the rejection of Columbus’s ideas by scholarly clergy in the hallowed halls of the University of Salamanca; an offer of support from boat-builder Martín Pinzón at a map dealer’s in Seville; the leap-of-faith contract struck with Queen Isabela after Spanish victory over the Moors in Granada in January 1492; and the departure of the Niña, Pinta, and Santa María from Palos de la Frontera seven months later. Part 2 plays out the deception, tensions, near mutiny, and ultimate good fortune (for the duplicitous, less-than-honest Columbus at any rate) of the ten-week Atlantic crossing, which resulted in the world’s most (in)famous geographical “discovery.” Part 3 dwells little on Columbus’s short-lived achievements but concentrates instead on his abject, long-term failures, for he finds to his grief (and that even more so of the native peoples subject to his and others’ exploitative rule) that the perils of navigation have their terrestrial equivalent in the form of ill-fated, disastrous government. Seven ruinous years end with Columbus being removed from office by Francisco de Bobadilla, whom he had earlier rebuked and thus made an enemy of. Sent home in chains as well as in disgrace, it is left for Columbus’s son, Hernando, to clear his father’s name, which he did by writing the first biography of the explorer while at the same amassing the greatest private library (15,000 titles) of his day (Wilson-Lee 2018). Meanwhile, others claim the riches and recognition that eluded the Admiral of the Ocean Sea: Las Indias, the Indies, eventually become known as “America,” after the Florentine navigator Amerigo Vespucci, not “Columbia” after the Genoese Cristoforo Colombo, better known in his day as Cristóbal Colón.

Sauer’s The Early Spanish Main (1966), the magnum opus of the dean of our discipline, endures as the most accomplished historical geography of the era, his contemplation of the larger significance of Columbus’s actions (like so much of Sauer’s oeuvre) light years ahead of its time. If Scott borrows from Sale, Sale in turn borrows (selectively and not always accurately) from Sauer. Also noteworthy is the volume of essays edited by Karl W. Butzer (1992). Charles Mann’s 1491 (2005), itself inspired by a perusal of Butzer’s edited volume, distils the findings of generations of Latin Americanist geographers in an accessible and absorbing exposition.

Post-colonial and Contemporary Scenarios

Argentina

Camila (1984), directed by María Luisa Bemberg.

“Ladislao, are you there?” asks the O’Gorman daughter who has disgraced her well-off family and provoked national outrage by falling in love and eloping with a priest. “By your side, Camila,” the fallen Jesuit replies before the shots of the firing squad ring out. The blood-soaked bodies of the blindfolded couple, Camila eight-months pregnant, her unborn child baptized by the holy water she had been given before the execution, are placed together in a makeshift coffin, three casualties of an Argentine state that was to have no better fortune in the twentieth century than in the nineteenth in resolving its tortured convulsions, political as much as personal.

Doomed from the outset, the romance between Camila and Ladislao Gutiérrez unfolds against the backdrop (indeed becomes a metaphoric illustration of) the dictatorship of Juan Manuel de Rosas, who ruled Argentina with authoritarian excess in the 1830s and 1840s, when his Federalist Party governed with the caudillo (strongman) at its helm. Camila’s father, Adolfo, is one of Rosas’ staunchest supporters, banishing his daughter to her room even for voicing concerns at the dinner table about Rosas’ tyrannical heavy-handedness. After he learns of Camila’s elopement, O’Gorman himself writes to Rosas, asking that the two lovers be hunted down and shown no mercy, the only way to restore both family honor and Federalist dictates of law and order. Meanwhile, the enamored pair finds refuge and solace far from the hubbub of Buenos Aires, posing as husband and wife while teaching school in a remote village in Corrientes province. There, alas, Ladislao is recognized during Easter celebrations by a visiting priest, who declares “God does not forget his chosen. Do you hear me, Father Gutiérrez?” True identities disclosed, Camila and Ladislao are left to their fate, an episode that has reverberated in Argentine consciousness ever since.

Nominated for an Academy Award in 1985, Camila is a period piece in which details of time and place are rendered with a discerning eye, whether evoking the strategic escape of the star-crossed lovers, in which the Uruguayan port of Colonia fills in for Buenos Aires, or their short-lived bliss in (not-so) godforsaken Corrientes. Suzanna Pick’s interview with María Luisa Bemberg, translated and edited by Julianne Burton-Carvajal (1993/1994), contextualizes adroitly film, history, and the tumult of Argentine identity. The nation’s lack of social consensus is nowhere better examined than in Ezequiel Martínez Estrada’s tour-de-force, X-Ray of the Pampa (1933/1971).

La Historia Oficial/The Official Story (Argentina, 1985), directed by Luis Puenzo.

Buenos Aires, 1983. In the wake of the Falklands conflict, the worst of the Dirty War may be over. But the reckoning of Argentina’s ill-fated invasion to claim sovereignty of the Islas Malvinas, to say nothing of the rule of the generals that preceded hostilities with the United Kingdom, has just begun.

Alicia and Roberto are a happy, well‑to‑do couple. He is a successful businessman, she a high-school teacher of history. They have a five‑year‑old daughter, Gabi, whom they adore. Gabi is adopted: Alicia and Roberto, long married, are unable to have children of their own. Their world is complacent, stable, assured – sheltered from the political turmoil that has wracked Argentina for so many years. The despair of the mothers and grandmothers who demonstrate for the return of missing offspring in the Plaza de Mayo is far removed from the day-to-day concerns of Alicia and Roberto.

Alicia’s world begins to unravel when Ana, a long‑lost friend from schooldays, returns to Argentina after years in exile. Alicia learns of how Ana was tortured and forced to flee Argentina because of her relationship with a politically‑suspect partner. The horrified Alicia asks Ana why she didn’t report the incident to the authorities. Ana is astounded at Alicia’s naivety – to whom could she have turned when the authorities themselves are the ones responsible for apprehending, torturing, and killing thousands of “disappeared” citizens, an estimated 30,000 investigations now suggest?

Ana is suspicious of Gabi’s background. She tells Alicia that many “disappeared” women were captured while they were pregnant, giving birth before they were killed. Babies born of “disappeared” mothers were then sold to families prepared to ask no questions, or adopted by military officers and their associates. Alicia begins to fear that Gabi may be one such child.

Alicia decides to embark on a quest for the truth, no matter what it might reveal. She questions her husband. Unsatisfied with Roberto’s vague answers, she searches through hospital records. There she uncovers the identity of her daughter’s parents, who were indeed both “disappeared.” She meets and befriends the grieving woman who is Gabi’s grandmother. Equally as ominous, however, Alicia realizes that Roberto’s business dealings link him both to paramilitary forces and local and foreign entrepreneurs profiting from the government’s maintenance of civilian calm at the price of horrendous human rights violations.

In a disturbing climax, Alicia confronts Roberto with her discoveries. Roberto responds violently. As the film ends, their marriage is in ruins. And Gabi’s identity (and destiny) altered irrevocably.

Galeano’s Century of the Wind (1986/1988) contains three vignettes as poignant about the “disappeared” and their children as The Official Story. The courage of the women Galeano calls “The Granny Detectives,” who still demonstrate daily in the Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires, as well as the fate of thousands who were “disappeared,” never to be seen again, is lodged forever in the conscience of a nation.

Bolivia

Yawar Mallku/Blood of the Condor (1969), directed by Jorge Sanjinés.

To its confusion and distress, an indigenous community finds that its woman members are becoming increasingly infertile, no longer able to bear the number of children essential for family and group survival. The film depicts the tragedy as it afflicts the life of Ignacio, once a proud father, village leader, and a happy man devoted to the welfare of his wife, Paulina, and their offspring. After the couple’s children die from sickness, Paulina and Ignacio try to have more to replace them, but cannot understand why nature appears set against them. They consult a shaman who, divining coca leaves, speaks of an impediment: mother coca never lies. Ignacio retreats to the mountain, in search of illumination: he “fills himself with light” on the edge of an altiplano precipice, connecting Paulina’s (and scores of other women’s) inability to become pregnant with the arrival of an American medical mission. Ignacio concludes, in fact correctly, that “foreigners are sowing death in our women’s wombs” by sterilizing them after the unsuspecting women last give birth. Ignacio and his fellow villagers take revenge.

Much of the film is narrated in flashback, so viewers must be patient, as well as imaginative, as the action unfolds, piecing bits together just as Ignacio had to. Made on a shoe-string budget with mostly non-professional actors, parts of Blood of the Condor are rather wooden and unpolished, but bear documentary-style testimony. The film stands as a unique statement against the injustices, and inhumanity, of misguided development assistance, for the plot of the film stems from incidents that actually occurred. In the 1960s, U.S. medical teams carried out sterilization operations on indigenous women in Bolivia without their consent, not informing patients or partners about what was being perpetrated. The Progress Corps in Blood of the Condor is the real life U.S. Peace Corps, an organization that was expelled from Bolivia when its actions and complicity were uncovered.

The ever-resourceful Burton (1986) furnishes an engaging interview, “Revolutionary Cinema,” in which director Sanjinés addresses the challenges of making films in a country like Bolivia.

Brazil

Bye, Bye Brazil (1980), directed by Carlos Diegues.

The Caravana Rollidei embodies the Brazilian Dream. Members of its travelling show include (1) Lord Gypsy, a smooth‑talking con‑man magician; (2) Swallow, a mute, strong‑man truck driver; (3) Salomé, an exotic dancer who doubles, when necessary, as a prostitute; (4) Cico, a naïve, idealistic accordion player; and (5) Dasdô, his more practically‑minded and very pregnant wife. Brazil is depicted as a land of infinite opportunity, where anything is possible and everything can be attained, especially material enrichment. A shared belief in a rosy future one day surely to be theirs propels the Caravana Rollidei on through adversity, disillusion, disenchantment, and disaster. Collectively, in the thoughts and behavior of a handful of people, the rhythm of Brazil is adroitly captured, the fortunes of the Caravana Rolidei forever changing as it traverses the length and breadth of the nation.

Geographically, the film moves from the dry, impoverished sertão (backlands) of the Northeast to the frontier excesses of Altamira, then downriver to the bustling Amazonian port of Belem, and finally to the capital city of Brasilia. Everyone on the road has a story to tell – tragic, funny, sad, heartening, miserable, joyous, degrading, and uplifting. All Brazilian life is here, and we are left to marvel that so much ground can be covered, so much social, psychological, and physical terrain incorporated, in one single, giddying cinematic sweep.

Latin American stereotypes abound: the macho male; the subservient, sexually exploited female; Indians as victims, vestiges, or savages, destined never to be on an equal footing with other Brazilians; rural squalor, urban grandeur; whites in positions of power and authority, blacks forever left out. Myth and reality coalesce. Besides being the name that Lord Gypsy baptizes Dasdô and Cico’s baby girl, Altamira is conjured as a present‑day El Dorado, a place of wealth and abundance that people search for, but never find.

In her interview with director Diegues, Burton (1986) offers us an inside peek at “The Mind of Cinema Novo” that makes for engrossing reading.

Pixote (1980), directed by Hector Babenco.

If Bye, Bye Brazil is the Brazilian Miracle as elusive dream, then Pixote (slang for “little bastard”) is the Brazilian Miracle as inescapable nightmare. Made in documentary-style mode by the Argentinian émigré Hector Babenco, the following synopsis of the film comes from an interview with Babenco conducted by George Csicsery (1982), aptly titled “Individual Solutions:”

During a routine police sweep of São Paulo streets, Pixote (Fernando Ramos da Silva), an abandoned ten‑year‑old, Lilica (Jorge Julião), an effeminate adolescent, and other boys are taken to a juvenile detention center where they begin to learn the basics of survival in the face of police brutality, rape, and murder. When the web of intimidation and murder perpetrated by the police threatens to engulf them, several of the boys escape. Pixote, Lilica, and Diego (José Nilson dos Santos) find themselves on the street in a group led by Dito (Gilberto Moura), an older macho teenager who becomes Lilica’s lover. They pursue a life of petty crime until Lilica makes a sexual conquest of Cristal (Tony Tornado), a drug dealer who commissions the gang to make a cocaine delivery in Rio. In Rio they are swindled by adult criminals, but inadvertently get their revenge when Pixote stabs the stripper who stole their drugs. Her purse yields a gun and enough money for Pixote, Dito, and Lilica to buy the rights to an aging alcoholic prostitute named Sueli (Marilia Pera), who becomes a mother and lover to the boys. Using her as a decoy they casually mug her customers at gun point. The crime wave leads to the group’s most harmonious moments, until Lilica gracefully departs, his feminine role usurped by Sueli. One night during a botched mugging, Pixote kills both Dito and Sueli’s American client. For a moment Sueli contemplates escaping to the country with Pixote, but then rejects him. Pixote goes out on the streets to start a new life, with the gun in his belt. (Csicsery, 1982, p. 2)

The subject matter of Pixote, itself influenced by Luis Buñuel’s neorealist masterpiece Los olvidados (1950), where the delinquent setting is Mexico City not São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, spawned a genre of underdog “favela films,” among them Walter Salles’ Central Station (1998); Carlos Diegues’ Subway to the Stars (1987) and Orfeu (1999); Fernando Meirelles’ City of God (2002); and José Padilha’s Elite Squad (2007). All with substantial merit, none packs the punch of Pixote. In a tragic case of life mirroring art, Fernando Ramos de Silva, the “fictional” Pixote, was shot dead during a police raid on August 26, 1987. He was nineteen years of age.

Four Days in September (1997), directed by Bruno Barreto.

The September in question is that of 1969. Rather than usher in a short period of military rule, as many observers had anticipated, and some positively so, the 1964 coup d’etat that brought the dictatorship of the generals to power has instead spawned a repressive regime, one that shows no sign of relinquishing authoritarian rule. Its critics are routinely “disappeared” or are imprisoned, tortured, and executed. How can the tragedy that has befallen Brazil be communicated to the outside world when the national press is censored and freedom of speech, like so many other democratic values, removed and deemed subversive?

This is the dire situation that a group of idealistic young people, women and men barely out of their teens, decide to do something about. Fernando and César, who become Paulo and Oswaldo, join an urban guerrilla group, but their actor friend, Arthur, opts out of such a radical solution. A bank robbery to raise funds is only half-successful: money is seized, but there is a problematical snafu. Afterwards, Fernando/Paulo hits on the idea of drawing world attention to Brazil’s predicament by kidnapping the U.S. Ambassador, the luckless Charles Burke Elbrick. More seasoned, street-smart revolutionaries are brought in to help the rookies carry out the abduction.

The drama unfolds from Thursday, December 4 to Sunday, December 7, by which time guerrilla demands must be met or Elbrick will be killed. Suspense reigns. Two epilogues, one a month later, another eight months later, make Four Days in September edge-of-the-seat viewing.

The military ruled Brazil for twenty-one years, until a civilian government signaled a return to democracy in 1985, but a democracy in which the generals for years thereafter continued to exercise considerable clout. As they do still, today.

Brazilian and Peruvian Amazon

Fitzcarraldo (1982), directed by Werner Herzog.*

Fitzcarraldo, which echoes in many ways how he tackled the making of Aguirre, saw Werner Herzog and his film crew return to interior South America, where they marshal spectacular settings in Peru and Brazil to tell the epic tale of Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald, “Fitzcarraldo.” Thus far in life, Fitzcarraldo has failed to achieve two of his most recurring dreams: (1) constructing a trans-Andean railroad to connect the Amazon rainforest with the outside world; and (2) establishing in the tropics a factory that will make ice. Played by Herzog’s alter ego, the once again off-the-wall Klaus Kinski, Fitzcarraldo also yearns to construct an opera house, where his idol, Enrico Caruso, will be invited to perform. Securing money for the undertaking through the good services of his lover, Madame Molly, played by the alluring Claudia Cardinale, Fitzcarraldo gambles on a land option in hostile Indian terrain, which he believes to be abundantly stocked with natural rubber trees. Fitzcarraldo then converts a passenger steamship into a commercial vessel and persuades a group of natives to haul it over a mountain, from one river system to an adjoining one, in order to open up new tracts for rubber exploitation. The ship and Fitzcarraldo both make it over the mountain, but at a cost measured not just in human lives. Does the venture succeed or fail? Viewers must ponder the outcome for themselves.

Fitzcarraldo is an extraordinary film, a dizzying daydream, a mad fantasy from start to finish. The opera house featured in the film’s opening scenes is that of Manaus, built at the height of the nineteenth-century rubber boom (Barham & Coomes, 1996). Like European intrusion and misadventure in the first place, Herzog’s strategies of turning Indians into film protagonists was fraught from the beginning with all sorts of logistical setbacks, to say nothing of moral dilemmas. Burden of Dreams (1982), a documentary by Les Blank about the making of Fitzcarraldo, leads viewers to wonder whether Herzog the director is even more demented an artist than Kinski the actor. The latter’s autobiography, Kinski Uncut (1996), recounts his version of the making of Fitzcarraldo, offering a scathing account of the actor’s dealings with both filmmakers.

(*) This synopsis leans heavily on the entry for Fitzcarraldo in Schwartz (1997).

Chile

Missing (1982), directed by Costa-Gavras.

Americans Charles Horman and his wife Beth are a recently married, happy young couple. The harmony of their relationship, however, is not reflected in the fear and uncertainty that wracks daily life in their adopted South American home, an unnamed but unmistakable Chile. Real-life events are dramatically set in the immediate aftermath of the military coup of September 11, 1973, in which the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende was overthrown by the Chilean armed forces, headed by General Augusto Pinochet. The U.S. State Department still denies that it was involved in the coup. Secretary of State at the time of the coup, which took place when Richard M. Nixon was in the White House, was Henry Kissinger, whose actions and invective against the Allende government have since been documented by Christopher Hitchens (2001) as constituting “a case for prosecution on counts of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and offences against international law.”

One evening Beth fails to reach the safety of her house before curfew falls. She passes a tense night on the street. Upon returning home Beth finds that the Horman house has been ransacked and that her beloved Charlie is missing. She contacts her father-in-law, Ed, who comes to Beth’s assistance, convinced that his son must have been up to something. What Ed finds out leads him to think the contrary. His and Beth’s search for the missing Charlie sees them traverse a labyrinth of lies and duplicity that ends in an unwholesome revelation of the truth. “You play with fire, you get burned,” a high-ranking American military official tells Ed; Charlie, he implies, may simply have seen or known too much about what was happening, hence his being “disappeared” and murdered, one foreigner among thousands of Chileans who met the same ignominious fate.

Colombia

María, llena de gracia/Maria, Full of Grace (2004), directed by Joshua Marston.

María Álvarez, seventeen years of age, is a young woman with decisions to make. Her home life is crowded and tense, fraught with confrontation as she tries to assert herself while living cheek-by-jowl with her mother, grandmother, sister, and infant nephew. Responsible adult males are nowhere to be seen, not least in the character of María’s boyfriend, Juan. To the problems of family and a so-called relationship with Juan, things at work are just as bad, for María’s job – she plucks thorns from roses in a local nursery – is menial and unsatisfying. Frustrated if not disaffected by her small-town lot, María quits her job, splits with Juan, and falls out with her mother and sister. Crisis reigns.

A spin on the dance floor with the dashing Franklin leads to a lucrative but potentially dangerous option: that of transporting capsules of heroin to the United States. In Bogotá, María is taken through the drill, trained not as a solitary “mule” but as one member of a pack that also involves her friend Blanca from the flower factory and an acquaintance called Lucy. Arrival in New York does not unfold according to plan.

“These gringos don’t know a thing,” María’s dealer had assured her back in Colombia. It turns out they do. Crisis reigns again.

“America is too perfect, too straight.” Lucy’s words could not be further from the truth. Her sister, Carla, seeks the counsel of another Colombian living in New York, Don Fernando, in real life Orlando Tobón: he’s “Mr. Fix It,” and actually plays himself (Kilgannon, 2004; Wilkinson, 2007). Carla and Don Fernando become enmeshed in María’s predicament as she struggles to find a way out.

“It’s what’s in you that counts” we discern on a billboard that María walks past at the airport, seeing off Blanca on her return to Colombia. Mother-to-be María stays behind, carrying the future with her. The narco-geography that pervades Latin America, where it takes more lives than any other malaise, is nowhere enacted with such fine-grained attention to detail, and everyday resonance, as in this somber film.

El Salvador

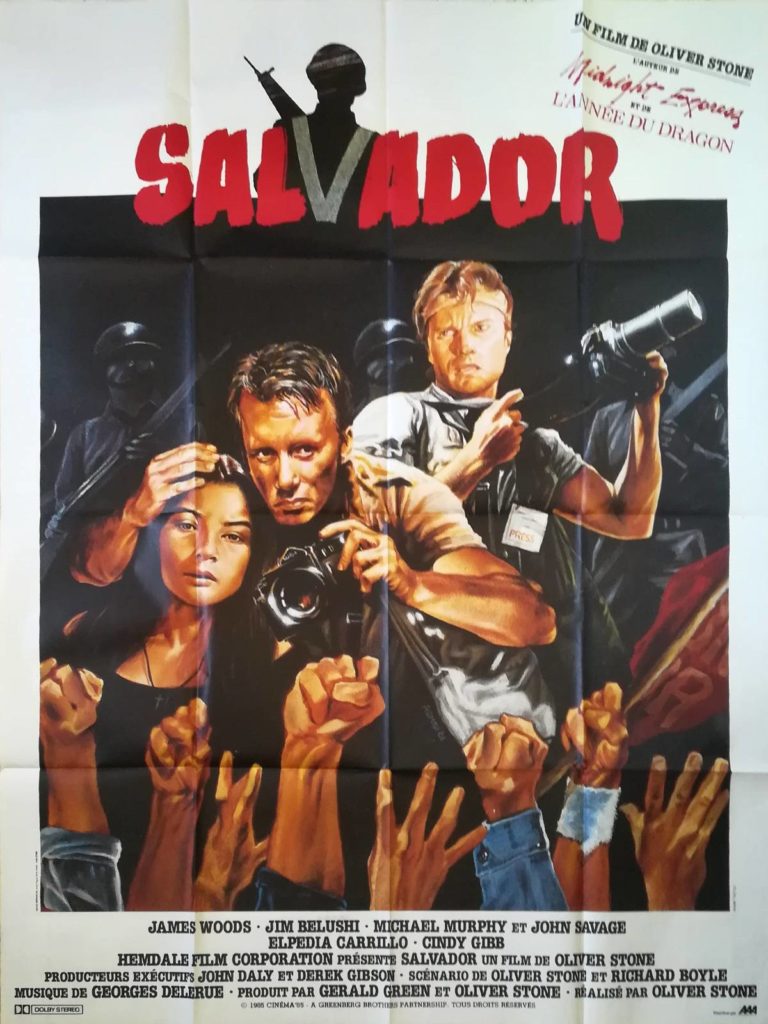

Salvador (1985), directed by Oliver Stone.

Set in war-torn El Salvador in the early 1980s, Salvador is a seedy film about American involvement in Central America and the role of the media in portraying events then taking place. Stone deploys the film to critique the atrocities carried out by the Salvadoran armed forces, backed by U.S. military and political personnel, in the Cold War fight against alleged communist intervention. The venal hypocrisy of American foreign policy figures prominently in Stone’s exposition. Fictionalized episodes follow real-life chronology, highlighting pivotal incidents in a brutal civil war that claimed an estimated 75,000 lives.

The action revolves around photojournalist Richard Boyle (James Woods) and his protégé, an out-of-work disc jockey called Dr. Rock (Jim Belushi). Boyle’s character elicits a love-hate response from the viewer. On the one hand, he is a sleazy, low-life reprobate who uses people constantly. On the other, Boyle’s fearless bent furnishes his clientele with reportage none of his competitors can even approximate. “You have got to get close to get to the truth,” he asserts. “If you get too close, you die.” Boyle sees his job to get as close as he can. His fellow journalists get their scoops while drinking beer and eying up the girls at the Camino Real Hotel, where their “informed sources” are U.S. military advisors and high-ranking members of the Salvadoran army. Boyle stomps (to) a different beat.

How to elicit accurate and reliable media coverage is addressed, if not resolved. Boyle, whether or not we like him, is an old hand at getting out the story. That U.S. aid to El Salvador was not cut off until word got out about the rape and murder of four American nuns on December 2, 1980, indicates the pivotal role of the media in molding public opinion. It also demonstrates the sad reality that only after four American lives are lost can the slaughter of so many more Salvadorans be comprehended, if not taken seriously. The relationship between blood and ink in the western media is as unjust as the geographies of inequality that perpetuate poverty in Central America in the first place.

Guatemala

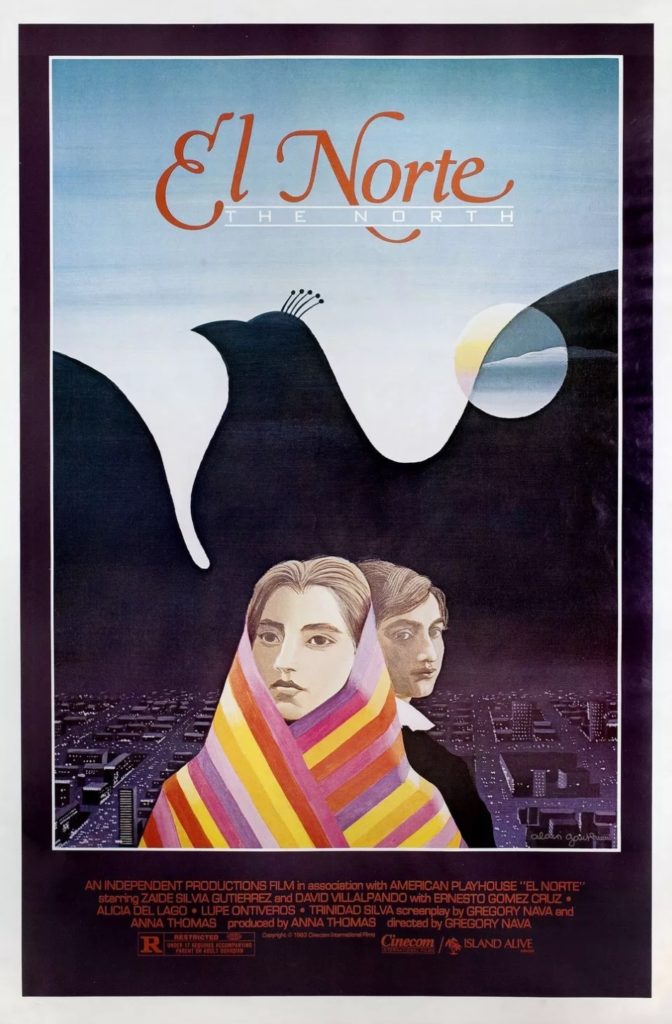

El Norte (1983), directed by Gregory Nava.

“Where some have found their paradise, others just come to harm.” So runs a line in “Amelia,” a song that Joni Mitchell wrote in tribute to the intrepid solo pilot Amelia Earhardt. The song, from the road album Hejira (1976), echos the flight for something better that lies at the heart of bittersweet El Norte.

I happened to be attending a conference organized by the Newberry Library in Chicago when El Norte was released. It was a bitterly cold December evening when I emerged on to Michigan Avenue after what the Fine Arts Theater billed as a World Premiere Engagement. I walked back to my lodgings frozen to the bone, but with my heart warmed by the film’s lustrous beauty. I felt I had seen and been moved by a magnificent film, and wondered what kind of review it would receive from the celebrated Chicago film critic, Roger Ebert.

“From the very first moments of El Norte, we know that we are in the hands of a great movie,” Ebert wrote in the Chicago Sun‑Times on December 15, 1983. “It tells the story of two young Guatemalans, a brother and sister named Enrique and Rosa, and of their long trek up through Mexico to El Norte – the United States. Their journey begins in a small village and ends in Los Angeles, and their dream is the American Dream.” He continues:

The movie begins in the fields where Arturo, their father, is a bracero– a pair of arms. He goes to a meeting to protest working conditions and is killed. Their mother disappears. Enrique and Rosa, who are in their late teens, decide to leave their village and go to America. They travel by bus and foot up through Mexico, which is as harsh on immigrants from the South as America is. At the border they try to hire a coyote to guide them across, and they finally end up crawling to the promised land through a rat‑infested drainage tunnel. Los Angeles they first see as a glittering carpet of lights, but it quickly becomes a cheap motel for day laborers, and a series of jobs in the illegal, shadow job market. Enrique becomes a waiter. Rosa becomes a maid. Because they are attractive, intelligent and have a certain naive nerve, they succeed for a time, before the film’s sad, poetic ending (Ebert, 1983, para. 4-6).

Cary Joji Fukunaga’s Sin Nombre (2009) may have reconfigured Central American immigrant plight, and regionalized more a parlous situation, but El Norte remains a worthy film, prescient and prophetic, well deserving of the “two thumbs up” the judicious Ebert accredited it.

Men with Guns (1997), directed by John Sayles.

Dr. Humberto Fuentes is a resolute man of science. Close to retirement, the good doctor has dedicated himself, life-long, to his profession, avoiding entanglement in the political upheaval tearing apart the unnamed country in which he practices, unequivocally Guatemala at the height of its thirty-six-year armed conflict (1960-1996). The proud physician once trained a group of his very best students to serve in remote parts of the country he himself has never been to. Fuentes seldom strays from the comfortable confines of the capital city, so awareness of the atrocities that stalk rural areas rarely register on his urban, and urbane, sensibilities. He’s brilliant, but blinkered.

All that changes when Fuentes bumps into his star student, Bravo, whom he discovers is working in a poor neighborhood dispensing medicines. “Why are you not working in the countryside with the others?” Fuentes inquires. The scornful Bravo replies, “Ask Cienfuegos and he’ll tell you why.”

Fuentes sets out the next morning in search of Cienfuegos. When he reaches the village where Cienfuegos is said to live, Fuentes is told that Cienfuegos has been murdered by “men with guns.” Sayles constructs the doctor’s voyage of discovery as an allegory of life and death. The individuals and groups he encounters (the Salt People, the Sugar People, the Coffee People, the Banana People, the Gum People, the Corn People, and finally the Sky People) reveal a country whose killing ways force Fuentes to confront a dark reality he has never before suspected, or taken the trouble to find out about. When he finally approaches the refuge known as Cerca del Cielo, Close to Heaven, his epiphany draws to a close.

Honduras (Guatemala and Mexico)

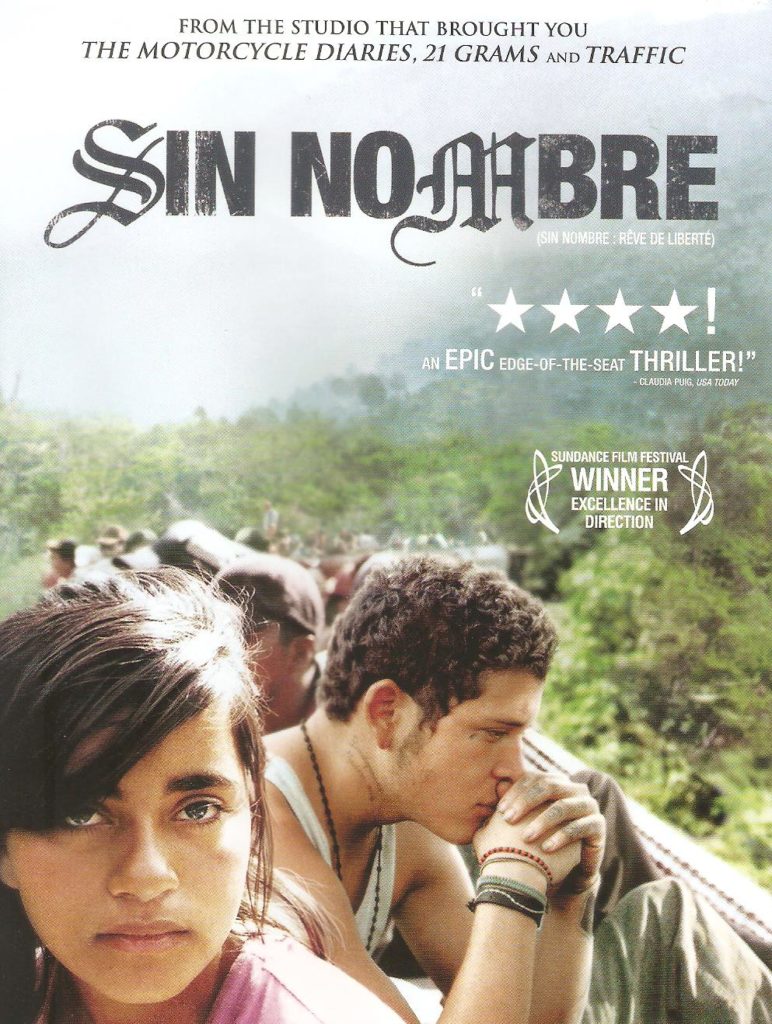

Sin Nombre/Without A Name (2009), directed by Cary Joji Fukunaga.

For the disadvantaged of Mexico and Central America, negotiating passage to the United States is never easy, legal or otherwise. In the case of Willy, better known by his gang name of El Caspar, and the innocent but quick-thinking Sayra, their situation is made even more hazardous by the fact that El Caspar is fleeing the retribution of his former associates in the Mara Salvatrucha, perhaps the most notorious gang in the region. Destiny has served them an impossible hand, but they chance it nonetheless. Will their fate be different once they reach the U.S. border, and cross over (like Enrique and Rosa in El Norte) into the promised land?

The film opens with El Caspar overseeing the rite of passage into the Mara Salvatrucha of El Smiley, still only a boy. His grandmother, try as she might, can do nothing to stop him from being inducted. In Tegucigalpa, Sayra gets to meet her father, with whom she journeys overland from Honduras through Guatemala to Tapachula, Mexico. There the train to the future, La Bestia (The Beast), is waiting. Sayra boards it with motives quite distinct from those of El Caspar, who finds himself thrown to her rescue. A bond is formed as the train winds its way north, pursued by El Smiley and members of the Mara Salvatrucha, bent on settling scores with El Caspar. Romance is on the rails, doomed in more ways than one.

The youth of the so-called Northern Triangle (El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras) are left to fend for themselves in a toxic, brutalized, unforgiving landscape not of their design or choosing, but one they must traverse and try to survive in nonetheless. There are no easy options, only day-by-day decisions to be made in the fine line between life and death, wafer thin not only for Sayra and Willy but also for millions more like them.

Mexico

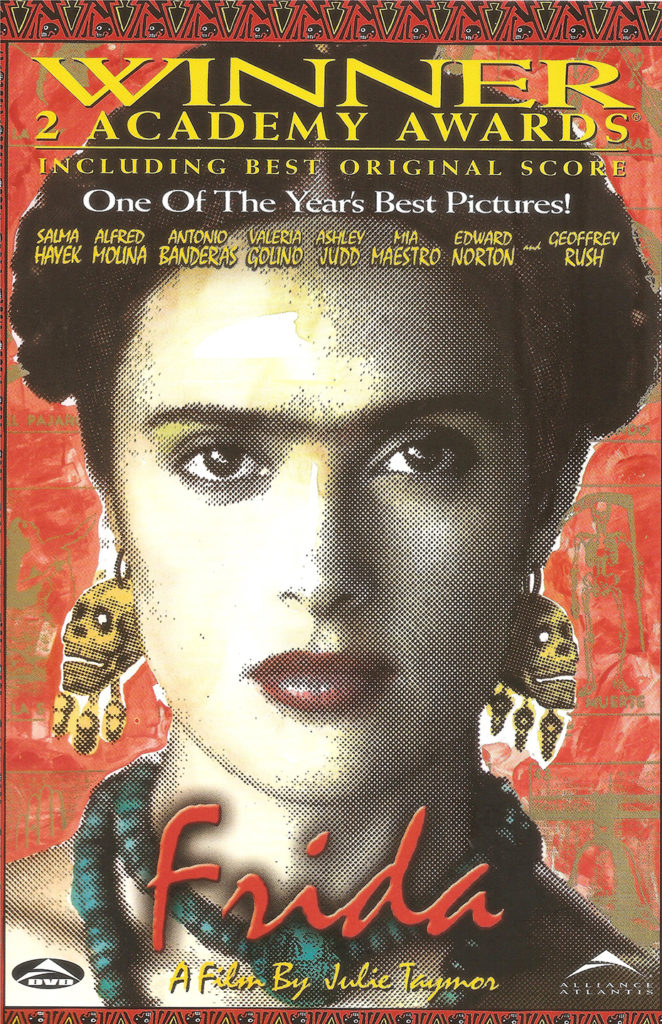

Frida (2002), directed by Julie Taymor.

“I miss …. us, Frida.” The words are uttered, forlorn and melancholic, heartfelt and sincere, toward the end of the film by the man she once dared call “Panzón,” Potbelly. Her designation was voiced when (as a young art student) she snuck in to see him paint – then witness him seduce the naked model posing for him. It was hardly a conventional episode of love at first sight, conventions being the antithesis of how both chose to live, but it was love nonetheless – one that would see Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) twice marry (a divorce in between) the larger than life (his girth was aptly invoked) Diego Rivera (1886-1957), Mexico’s greatest artist.

Julie Taymor’s biopic is based on Hayden Herrera’s moody biography (1983), both works offering a panorama of Mexico in the wake of its violent revolution (1910-1920), which saw the country begin the second decade of the twentieth century with a population of 15.1 million and end it with 600,000 fewer. Rivera captured the turmoil of the nation in some of his greatest murals; Kahlo’s depictions of turmoil are inner, far more personal, depicting the angst of her wounded body (she had polio as a child and was severely injured in a bus crash as a teenager) and her pain of being alone in the world despite always being surrounded by family, friends, fellow artists, political activists, and bisexual suitors. It was her soulmate Rivera – she expected loyalty if not fidelity from him – who convinced Kahlo of her innate talent at the outset, and who stood by her throughout, transgressions and all, in her commitment to art.

As husband and wife the two go to New York, where Nelson Rockefeller has commissioned Rivera to produce a mural, “Man at the Crossroads,” later destroyed because of Rivera’s refusal to bow to Rockefeller’s insistence that he eliminate Vladimir Lenin from what he has depicted. The confrontation epitomizes Mexico’s eternal standoff with the United States. Kahlo’s crisis while in “Gringolandia” is visceral, not ideological, a miscarriage almost killing her. Mexico beckons them back, but each goes their separate way, yet united still. Rivera is there as Kahlo is wheeled in, literally on her deathbed, at the exhibit of her work she longed to have in her homeland.

“I hope the end is joyful,” are Frida Kahlo’s departing words. “I wish never to return.”

Y Tu Mamá También (2001), directed by Alfonso Cuarón.

Julio (Gael García Bernal) and Tenoch (Diego Luna), the youthful protagonists of Y Tu Mamá También, inhabit a Mexico of their own whimsical creation. Tenoch’s background is privileged: his well-to-do family has even lived in Canada, one of Mexico’s NAFTA partners, his father having been dispatched to Vancouver for a spell while the heat of a scandal in which he was embroiled died down. Julio’s social origins are less auspicious, but fate having thrown them together he is happy to accompany Tenoch on the joy ride they embark upon. The two friends horse around, party hard, smoke dope, fornicate, fart, and masturbate without a care in the world. Meanwhile, other Mexicos an off-screen narrator informs us about scream in silence, barely registering on Julio and Tenoch’s weeded-out consciousness. Only when Luisa (Maribel Verdú) enters their lives does a grounded sense of reality intrude, and shake things up. Hard lessons are learned on the road to Boca del Cielo. Knocking on Heaven’s Door, they gain entry, become a ménage à trois, and enjoy a drunken one-night stand. The following morning, they part company. Somehow Mexico endures, but casualties are incurred along the way.

A frank, sexually explicit, morally disconcerting mediation on individual behaviour as well as class values and national mores, Y Tu Mamá También engages head on a nagging Mexican concern: the enormous costs of modernization, most recently in the guise of globalization and neoliberal reform, and the high price of human survival.

Nicaragua

Under Fire (1983), directed by Roger Spottiswoode.

When we watch the TV news at night, what criteria determine the content of our viewing? As one announcer reads or another asks questions, what story is being told, what really is being inquired about? How are the rules of the game agreed upon, and how do we know if or when they’ve been broken? Can reporters whose job it is to cover an event be trusted to do so responsibly? Is it possible for them, ever or always, to be objective and detached? Is there anything wrong if they are not?

Donald Trump’s trope of fake news had its precedent in Central America decades ago when another U.S. president, Ronald Reagan, held sway. Temporally, Under Fire is set prior to Reagan assuming power, in 1979, the year Sandinista revolutionaries in Nicaragua mounted an offensive that led to the overthrow of the U.S.-supported dictator, Anastasio Somoza, in July of that year. In the film, the dictator’s days seem numbered until a rumor circulates that the chief guerrilla commander has been killed. Without him the revolution could lose steam, falter, and come to naught. Is he dead or alive? Three American reporters make it their task to find out. In so doing they compromise what hitherto they considered inviolable ethical conventions. One of them, a photojournalist, declares: “I take pictures; I don’t take sides.” Later, after people he knew are killed, as justification for conduct deemed “unprofessional,” he confesses: “I guess I just saw one too many bodies.”

One body he did not count on seeing is that of his close associate, a fictionalized composite of the real-life Bill Stewart, the ABC newsman whose murder by Somoza’s National Guard on June 20, 1979, was filmed by his cameraman, Jack Clark, as it actually occurred. Somoza’s days were numbered after Clark’s footage went viral. But why should the death of one American, a local asks poignantly, the film implicitly too, mean more than the death of tens of thousands of Nicaraguans?

References

Adorno, R. & Pautz, P. C. (1999). Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca: His Account, His Life, and the Expedition of Pánfilo de Narváez. 3 vols. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press.

Balkan, E. L. (2011). The Wrath of God: Lope de Aguirre, Revolutionary of the Americas. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Barham, B. L. & Coomes, O. T. (1996). Prosperity’s Promise: The Amazon Rubber Boom and Distorted Economic Development. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Bishop, M. (1933). The Odyssey of Cabeza de Vaca. New York: Century Company.

Blank, L. (1982). Burden of Dreams. New York: The Criterion Collection.

Burton, J. (Ed). 1986. Cinema and Social Change in Latin America: Conversations with Filmmakers. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Butzer, K. W. (1992). The Americas before and after 1492: Current Geographical Research. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 82 (3).

Caraman, P. (1976). The Lost Paradise: The Jesuit Republic in South America. New York: Seabury Press.

Csicsery, G. (1982). Individual Solutions: An Interview with Hector Babenco. Film Quarterly, 36 (1), 2-15.

Davis, D. J. (2001). Review of Como era gostoso o meu francés/How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman. American Historical Review, 106 (2), 695-97.

Dempsey, M. (1987). Light Shining in Darkness: Roland Joffé on The Mission. Film Quarterly, 40 (4). 2-11.

Ebert, R. (1983, December 15). Review of El Norte.Chicago Sun‑Times. Retrieved from https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/el-norte-1983

Galeano, E. (1985). Memory of Fire I: Genesis. (Cedric Belfrage, Trans.). New York: Pantheon Books. (Original work published 1981)

Galeano, E. (1987). Memory of Fire II: Faces and Masks. (Cedric Belfrage, Trans.). New York: Pantheon Books. (Original work published 1984)

Galeano, E. (1988). Memory of Fire III: Century of the Wind. (Cedric Belfrage, Trans.). New York: Pantheon Books. (Original work published 1986)

Herrera, H. (1983). Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo. New York: Harper and Row.

Hitchens, C. (2001).The Trial of Henry Kissinger. London: Verso.

Kilgannon, C. (2004, August 5). Playing Himself, the Drug Mule’s Last Friend. The New York Times.

Kinski, K. (1996). Kinski Uncut. New York: Viking.

Long, H. (1987). The Marvellous Adventure of Cabeza de Vaca. London: Picador. (Original work published in 1936).

Mann, C. M. (2005). 1491: New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Martínez Estrada, E. (1971) .X-Ray of the Pampa. (Alain Swietlicki, Trans.). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. (Original work published in 1933).

Mitchell, Joni. (1976). Hejira. Asylum Records.

Minta, S. (1993). Aguirre: Recreation of a Sixteenth-Century Journey across South America. London: Jonathan Cape.

Pick, S. M. (1992/1993). An Interview with María Luisa Bemberg. (Julianne Burton-Carvajal, Trans.). Journal of Film and Video: Gender Perspectives in Latin American Cinema, 44 (3/4), 76-82.

Said, E. (2000). Culture and Imperialism. New York: Vintage Books.

Sale, K. (1990). The Conquest of Paradise: Christopher Columbus and the Columbian Legacy. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Sauer, C. O. (1966). The Early Spanish Main. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Scholfield Saeger, J. (1995). The Mission and Historical Missions: Film and the Writing of History. The Americas, 51 (3), 393-415.

Schwartz, R. (1997). Latin American Films, 1932-1994: A Critical Filmography. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland Publishers.

Wilkinson, A. (2007, November 26). The Patron: The Man to See in Little Colombia. The New Yorker.

Wilson Lee, E. (2018). The Catalogue of Shipwrecked Books: Young Columbus and the Quest for a Universal Library. London: William Collins Books.

[1] These film synopses accompany W. George Lovell’s (2019) JLAG Perspectives essay entitled “Latin America on Screen: Film as a Complement to Teaching Regional Geography,” available here: http://muse.jhu.edu/article/729123.