Mina Moscatelli 2021 Field Report

Bamboo and Smallholder Livelihoods in the Coastal Region of Manabí, Ecuador

Abstract:

The global bamboo market has been continually expanding in recent years, with an emerging focus on Latin America and its naturally growing bamboo. In the coastal region of Manabí province Ecuador, natural groves of guadua angustifolia bamboo—a strong, durable, woody bamboo, used most notably for construction purposes—are found on rural smallholder properties. These native outcroppings of bamboo are in the early stages of being targeted for extraction by local, regional, and global companies and governments promoting sustainable development. However, limited research exists regarding the reality on the ground and the current potential for bamboo in Latin America, much less Ecuador, to be harvested sustainably and in such a way that benefits local communities and economies. This research will be guided by the conceptual frameworks of political ecology with a focus on the political economy of Latin America and Ecuador and cultural geography of smallholders and bamboo within the landscape of Manabí. Using qualitative methods (i.e., semi-structured interviews, participant observation, fieldnotes) and analysis (i.e., transcription and coding of collected data), this research aims to examine the role of bamboo in coastal Ecuadorian livelihoods. Furthermore, research findings will serve to inform bamboo policy in Ecuador and Latin America.

Keywords: bamboo; Ecuador; political ecology; smallholders

Research Report:

Fieldwork Experiences:

Although summer research plans (to spend 6-8 weeks in Manabí) were postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, I was able to spend 4 weeks in Manabí carrying out research from November 11 to December 10, 2021 (during my fall semester). I conducted a total of eleven semi-structured interviews with a total of twelve participants in Manabí to capture the subjective relevance of how bamboo is understood, and what bamboo means to smallholders in Manabí on an individual and local level. Individuals were identified through snowballing recruitment from in-country connections of Dr. Zoe Pearson’s (my advisor) as well as people I encountered while in Ecuador. Interviews were conducted in Spanish as that was the primary language of my participants and I too have Spanish language fluency having received my Bachelor of Arts in Spanish language and culture. An interview guide was used during interviews to assure a level of consistency throughout every interview.

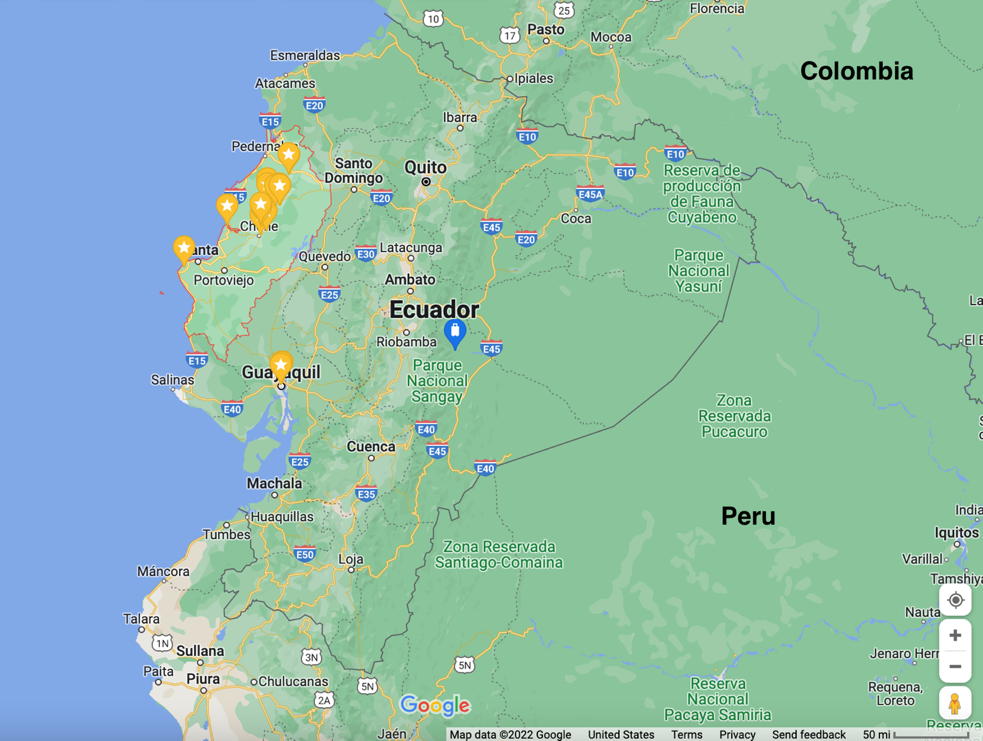

All my official interview participants were coastal Ecuadorian smallholder landowners with naturally growing bamboo on their properties. Five of the twelve participants had a primary form of income that was not farming and/or livestock based. The five primary occupations included a veterinarian, a local politician, a son who worked for his family’s chifle (fried plantain chip) manufacturing company, a public sector employee, and a lawyer. The other seven participants relied on farming and/or livestock to make a living. Participants ranged from ages twenty-three to seventy-six and included both males (nine) and females (three). Although my sample size was small, it is relatively representative of the smallholder population in Manabí as it included participants of both genders within a wide range of age and occupation. More so, my participants had some range in geographic area. Four participants were outside the city of Chone (approximately fourteen miles southwest of the Regeneration Field Institute—RFI), five were in or near the city of Flavio Alfaro (approximately twenty miles northeast of RFI), one was outside the city of Eloy Alfaro (approximately eighteen miles northwest of RFI), and two were in or near the city of Chibunga (approximately one-hundred-forty miles northwest of RFI). It should also be noted that saturation was reached as I began to hear the same responses from participants I interviewed.

Participant observation was conducted throughout Manabí province on a regular basis. More detailed participant observation occurred on smallholder properties within bamboo groves and while walking around smallholder properties. Participant observation contextualized coastal Ecuadorian relationships to, and understandings of, bamboo and its production process. It informed other livelihood processes as well and allowed me to reflect on my own positionality (Kearns 2016). Participant observation helped me answer my research questions and further observe and experience Ecuadorian smallholders’ lives as I recorded details about the complex social processes (Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw 2011) surrounding bamboo.

Fieldnotes complemented participant observation. I carried a small notebook with me everywhere to record fieldnotes. I noted cultural experiences and observations throughout daily activities and travel. I combined these notes with the notes I took during every semi-structured interview to ensure I have captured the entire data collection process each day. I combined and reflected on my daily observation notes and interview notes each night when typing them into my computer. My fieldnotes therefore detail what I observed and experienced while immersed in the interactions and processes of everyday life and fieldwork (Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw 2011; Kearns 2016). The practice of regularly taking fieldnotes and reflecting and recording them every night helped me understand preliminary findings and acted as a form of backing-up collected data.

I learned so much from being in the field and later data analysis. I found that bamboo plays an essential role in smallholder livelihoods. More so, smallholders have been subject to perpetual marginalization, exclusion, and exploitation, notably in relation to the development of natural resource markets in the capitalist global economy. For these reasons, smallholders have the most at stake as the bamboo market slowly begins to expand into Manabí. Having the most at stake, it is invaluable to champion the voices of smallholders within mainstream bamboo research and bamboo policy creation. Inclusion of smallholders in bamboo policy and development is the only way for the bamboo market to expand in such a way that benefits all parties, namely, the bamboo market itself, coastal Ecuadorian smallholders, and the natural environment of Manabí. Not only that, but serious consultation with and inclusion of smallholders in bamboo policy (from creation through implementation) will create spaces for marginalized populations to be given a voice in shaping policy that effects their livelihoods, something they have historically been denied, as well as the capability for the bamboo market to achieve true sustainability measures.

How Funds were spent:

Funds were used for lodging, printing, transcription services, data analysis subscription, and daily food and transportation costs. I used CLAG funding for half of my lodging expenses at RFI ($376). RFI acted as my home base for conducting many of my interviews in the rural areas in and around Chone, Manabí, Ecuador. I spent a total of 16 days at RFI at a rate of $47 per day, totaling $752. The other half of my RFI lodging costs were covered by other grant funding sources. I spent about $38 to print my transcripts to do some preliminary data analysis ahead of the CLAG Conference (which was ultimately postponed until 2022). I spent approximately $205 to have my interview recordings transcribed by a trusted Ecuadorian women based in Quito (she has done transcriptions for Dr. Pearson in the past). A MAXQDA 6-month Student Pro account, used to code and analyze my data cost $50. The rest of my CLAG grant was spent on daily food and transportation costs (averaged at about $17 per day). See the table below for more detail on how I used CLAG funding.

Achievement of Objectives:

I successfully achieved many of my objectives. I traveled to Ecuador and carried out an ethnographic exploratory case study design. I fell short of the number of interviews I had hoped for, but I was still able to reach saturation and obtain enough interesting and useful data to write a compelling thesis. I was not able to conduct focus groups as originally planned (due to COVID-19 and a shorter fieldwork period), but I conducted semi-structured interviews, participant observation, and fieldnotes as planned. I finished all my graduate school requirements and successfully defended my thesis on April 22, 2022. I graduated on May 14, 2022, with a master’s degree in International Studies from the University of Wyoming. The fieldwork in Ecuador, final thesis, and ultimate graduation would not have been possible without the generous grant funding from CLAG. In the future I hope to stay involved with the larger collaborative bamboo project (which my research is a part of). And starting in the fall of 2022 I will begin my second MA program at the University of Wyoming in Spanish language.

Photos:

Works Cited:

Emerson, Robert M., Rachel I. Fretz, and Linda L. Shaw. 2011. “Chapter 1: Fieldnotes in Ethnographic Research.” In Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes, 2nd ed. Chicago Guides to Writing, Editing, and Publishing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kearns, Robin A. 2016. “Chapter 15: Placing Observation in the Research Toolkit.” In Qualitative Research Methods in Human Geography, edited by Iain Hay, 313-333. New York: Oxford University Press.

Please see the full report for more details.